If PBS executives ever decide to launch their own version of SATURDAY NIGHT LIVE, they should choose Halley Feiffer’s new play as its season opener.

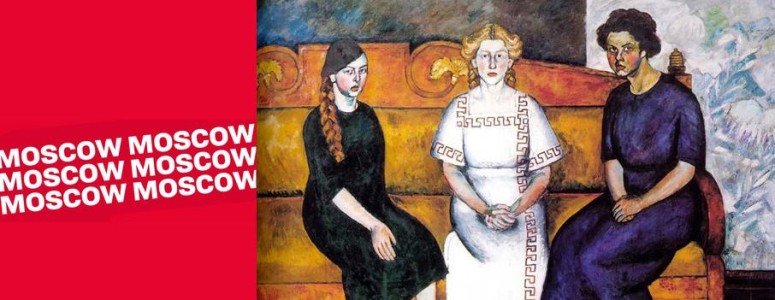

MOSCOW MOSCOW MOSCOW MOSCOW MOSCOW MOSCOW, now at the MCC Theater Space, has a title that may seem more than a tad redundant.

Not really. In this riff on Anton Chekhov’s THE THREE SISTERS, Feiffer mocks the incessant number of times that Olga, Masha and Irina Prozorov mention Russia’s most populous capital city.

In case you need reminding (or an introduction), the sisters yearn to abandon their uber-rural home. Although their father feigned excitement when he told them “We’re going to the country!” they see it as no substitute for The Big Onion.

As the lights come up, you’ll know this isn’t Chekhovian business as usual. Chris Perfetti wears Masha’s trademark black dress, but this Chris is actually Christopher and not Christine. The man dons no wig to cement the illusion. Still, in performance he’s as feminine as the script requires.

Soon you’ll see atypical casting for Solyony, too. Matthew Jeffers states on his website that he “looks up to Peter Dinklage – literally” because “Dinklage is 4” taller.”

Was Feiffer or director Trip Cullman the one who suggested this type of non-traditional casting? Which or both demanded stylization whenever the characters laughed? When they hear a line they deem funny, they simultaneously exclaim “Ha-ha-ha!” at the same level and length; then they suddenly stop as if gags had been shoved into their mouths.

Olga starts the show with a profanity-laden speech replete with anachronisms. Later “You’re the bomb,” “Wait for it” and others will pepper the play. The whoopee cushion, twice put to use here, wasn’t in existence in “The Russian countryside. 1900” as the program tells us.

The playbill neglects to say that MOSCOW 6, as we’ll dub it here, keeps to Chekhov’s having Act Two occur year or so later and Act Three a year or so after that. In this 90-minute take, Feiffer’s choosing to eliminate intermissions and not mentioning significant time passing could prove head-scratching to THREE SISTERS newcomers.

Feiffer isn’t content to follow Chekhov’s template and deliver a wan adaptation. Traditionalists must concede that she’s clearly examined the play with a fine-combed brain. “I’m the one who does everything,” complains Olga. Chekhov would agree – although he didn’t have Olga make a comment after Irina says “Why am I so happy today?” Feiffer does: “Because you’re delusional.”

By this point, we may agree with Masha’s assessment of her sister — although we might not use the C-word as she does here.

On a lighter note, Feiffer includes a few measures of a Sondheim song (Don’t worry; it’s not “Send in the Clowns”) and a Whitney Houston hit. Kulygin sings the former and plays the latter on a piano.

Well, the poor soul has got to do something with his time, what with Masha cuckolding him. Feiffer keeps to Chekhov’s Kulygin: teachers shouldn’t make the mistake of marrying young and immature students who – at the time and only at the time — regard them as gods. (Ryan Spahn’s Kulygin does well in going right from denial to acceptance of his wife’s decision.)

Aside from one scene in which Kulygin sports pajamas that are emblazed with the logos of many Broadway shows, he wears a CATS T-shirt. Costume designer Paloma Young has put many in T-shirts; Olga gets a laugh when she decides to change from a certain one to a certain other.

Casting throughout the ages has often made Olga the least alluring of the sisters. The actually attractive Rebecca Henderson is one of those rare performers who can “act” herself into looking less desirable. (Getting to say such lines as “Even when I was born, I looked a little tired” helps.)

Irina gives Olga a compliment about her looks that’s such a minor one that we know she doesn’t regard her sister as pretty. And yet, Olga grabs onto the assessment as if it were a life preserver in the Arctic.

She’ll bring it up for the rest of the play. Yes, as a famous line in an equally famous film goes, “You use what you got.” Besides, Olga isn’t above giving a left-handed compliment of her own to the family’s long-time nanny-servant Anfisa (an efficient Ako).

Feiffer’s reason why Andrey asks Natasha to marry him isn’t as potent as his motive in Chekhov. There Andrey feels bad at the way Natasha’s treated at the birthday celebration and, as a quick fix to buoy her spirits, impulsively proposes marriage. Chekhov’s point is that one little incident can lead to a life of unhappiness and ruin. That’s more effective than Feiffer’s mentioning – as so many thousands have before her – that lust is the determining factor in a young man’s wedding (and bedding) a young woman.

As Andrey, Greg Hildreth is very effective. Too bad he’s in such a dour role, for he has one of the best smiles in the business.

As horrific as Natasha turns out to be – and Sas Goldberg adds a little more nafkeh than usual – Feiffer does sympathize to some degree. Her conception of Andrey is one who won’t even deign to look up from his book and answer his wife’s basic questions. When one spouse stops listening, the other often goes looking for someone who will.

Chekhov had Chebutykin bring Irina an expensive birthday gift just because he cares for her. Feiffer has Irina state that she regards it as his bribe in hopes that she might bed him as a reward. Later Feiffer comes out with another theory on why Chebutykin (the fine Ray Anthony Thomas) is so good to her. Could be, could be …

With Tavi Gevinson playing Irina, one can understand why so many in the play are in love with her. She has charm in addition to beauty.

The admirers include Tuzenbach, although Feiffer puts forth the possibility that he’s gay. Irina and Tuzenbach even baldly discuss the issue. Steven Boyer’s characterization shows that he does love her … and yet, it also hints that if he won her, part of his motivation would be to prove something to himself. Meanwhile, Gevinson’s body language tells us that she does indeed like Tuzenbach – and that “like” is many yardsticks away from love.

Feiffer isn’t through with the gay issue: Tuzenbach expresses romantic interest in Solyony. “I like you, too,” Jeffers says, jumping off the bench on which he’d been sitting. His perfect enthusiasm combined with split-second timing in moving his gluteus maximus are credits to both him and Cullman.

(We’ll see if this relationship has any chance of developing …)

Chekhov had Andrey discover “old university lectures” from his youth; Feiffer does better by having him find a diary from long ago. Reading it pains him; wouldn’t yours do the same if you were reminded of your naiveté and failure to become The Great You that you’d anticipated?

This is the scene where Andrey tries to converse with Ferapont, who’s much too old and deaf to understand him. Feiffer eliminated Chekhov’s funniest exchange. For after Andrey asks him “Have you ever been to Moscow,” Ferapont (a keeping-my-dignity Gene Jones) sincerely says “No, it was not God’s wish.” Yeah, blame it on Him …

There are marvelous in-jokes. With so many in the house, a flummoxed Olga eventually snarls “I get confused with all the names.” Which of us doesn’t when it comes to Russian literature? (Quick! Who’s Fedotik? Don’t know? No problem this time around; Feiffer’s dropped him from her script.)

Was it Cullman who decided on the football-stadium-like set-up with the audience on each side of the “gridiron”? This causes a problem when Solyony calls Irina “Bitch!” Those of us on the far side discovered that he didn’t mean it from the smile he flashed when he looked our way; those on the other side were in their rights to take him seriously.

At play’s end, we hear “If we had gone to Moscow, we would have been happy.” Feiffer essentially asks “Who or what has been stopping you?” Chekhov might answer “Inertia and fear.” Feiffer has no patience for that in her decidedly 21st century take.

So you may go along with the craziness or think Feiffer was crazy to mock a masterpiece. Those who have reverence for the play may grimly nod in agreement when Vershinin (a sensitive Alfredo Narciso) tells everyone “That’s what we’re here for – to suffer.” They may well find MOSCOW 6 analogous to that famous statement about an accident: you can’t look at it and you can’t look away.

And yet, Chekhov broke some dramatic conventions, so can we chastise Feiffer for doing the same? Still, for all the comedy in the piece, there are many stretches where there isn’t a laugh to be heard. Could it be because Feiffer wasn’t able to think of one? At such times, she’s content to stay close enough to the original that she seems to be delivering just another new but faithful translation.

But most of the time, MOSCOW 6 offers plenty of laffs. Chekhov might well have been the first to laugh at what Halley Feiffer has inferred or concocted. Didn’t he claim that his plays were comedies?