Wouldn’t a play with Josephine Baker, Margaret Sanger, Langston Hughes and Adam Clayton Powell have terrific dramatic possibilities?

After all, shows with Big Characters and Big Events are often the ones we find the most compelling. Take HAMILTON, THE LION IN WINTER, LES MISERABLES and A MAN FOR ALL SEASONS. (Millions of theatergoers have.)

But what about a play in which rather unaccomplished ordinary people only share an acquaintance with these four luminaries? Could they hold our interest?

In the case of BLUES FOR AN ALABAMA SKY, the answer is a solid yes. Pearl Cleage once again proves what that 1939 song states: “T’aint what you do; it’s the way that you do it.”

The action takes place up north of Central Park, when, as the noted names listed above suggest, the Harlem Renaissance was still in force.

The action mostly occurs in two apartments, each across the hall from the other. On one side of the stage is the living room shared by Angel, a chanteuse and Guy, a dress designer; on the other sits the kitchen of 25-year-old virgin Delia.

If you attend (which you should), sit on house-left where Angel and Guy reside. You’ll see much more action there, for when two people share a small space, you know there’ll be much more drama than there’ll be in the home of a single woman.

Angel and Guy aren’t romantically involved; she’s been seeing a minor mobster; he’s gay and unattached. We not only get the impression that Angel doesn’t love Guy but also that she may not be able to love anyone. Angel is much more interested in her singing career, and money and security.

Guy, though, certainly loves Angel. When she has troubles, which is most of the time (and mostly of her own doing), he’s there with his ample shoulder on which she can cry. And if Angel doesn’t stop in due time, Guy’s got another shoulder ready to shoulder the burden. He’ll tell her the bitter truth when she must hear it, but always with tenderness and optimism.

Why can’t she return the favors? No, Angel is constantly putting down his dreams of designing clothes for his oh-so-casual acquaintance Josephine Baker.

(You probably will, too.)

Into their lives comes Leland. Some people fall in (what they think is) Love at First Sight. Leland, who’s recently moved to Harlem from Alabama, has the experience just from seeing Angel sitting at the window in her living room.

(This may not be clear to theatergoers. Set designer You-Shin Chen would have done well to have included a window frame to let us precisely know where Angel precisely is.)

Leland’s a Christian fundamentalist so you can well imagine what happens when he meets the unabashed homosexual. What you probably can’t imagine is what will happen afterward.

Meanwhile next door, Delia wonders if she should get involved in a May-December romance with Sam, the local obstetrician. You may laugh when Delia says that she’s never wanted to get involved with a doctor. Don’t forget that back then those who practiced medicine weren’t the omnipotent millionaires that they came to be. That would be especially true of a doctor in Harlem.

These five people will interact and impact each other’s lives, partly because this was a time when people were more neighborly. None of them locks the front door, so those across the hall feel free to barge in without knocking. So even if those celebrities’ names weren’t ever mentioned, from this laissez-faire entrance policy you’d know this play takes place many decades ago.

Cleage’s drama often serves as a metaphor for the decline and fall of Harlem Renaissance. And yet, as impressive as her play is, it wouldn’t of course score as mightily if director LA Williams hadn’t assembled a strong cast.

Actually, he’s amassed a magnificent one. John-Andrew Morrison is wondrous as Guy, way ahead of his time in being out and very proud. No mincing Nellie, he. Morrison proves a statement well said in that 1968 commercial comedy FORTY CARATS: “People take their cue from you.”

The best characters change and convince us that they have. Morrison certainly does – and in more ways than one.

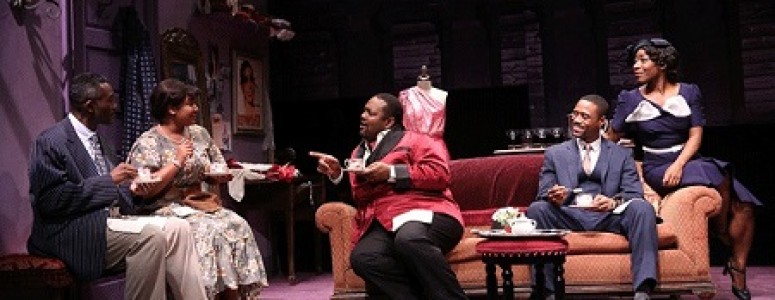

Alfie Fuller is a staunch Angel, whose narcissism is so strong that it long ago blinded her to the fact that she has it. Jasminn Johnson performs Delia in the best possible way, never seeming for a moment that she’s ACTING. As Sam, Sheldon Woodley stops us from being suspicious that he’s an aging roué and Khiry Walker has the sincerity for straight-arrow Leland.

When New York theatergoers attend and learn that Cleage wrote this play a quarter of a century ago, they may ask “How did I miss it the first time around?” They hadn’t; this is its initial New York production, thanks to Jonathan Silverstein’s ever-enterprising Keen Company.

BLUES FOR AN ALABAMA SKY runs through March 14, giving us another reason to beware The Ides of March. For among those plays and productions that deserve an extension, this is certainly one of them.