It offers one of the most stunning Act One finales in Broadway musical theater history and one of the greatest twists of fate ever seen in an Act Two opening.

That it also sports a galvanizing performance by Josh Young in the lead role helps immeasurably, too.

And yet, Amazing Grace should be much better than it is. But the book that Arthur Giron fashioned with Christopher Smith (who also wrote the music and lyrics) has the quality of those rural outdoor dramas that for decades have been dutifully conveying information to audiences without doing much for their emotions.

Too bad, for it also tells a hell of a story about John Newton, who metaphorically went to hell and back. It also becomes increasingly compelling as it goes along.

Amazing Grace starts out with a standard father-son conflict over what the lad should do with his life. This was no small matter in 1744 England, when sons were fully expected to obey to the letter what their daddies demanded.

Young John instead insists, “I don’t give a damn what the old man thinks.” He’ll go to sea as a crewman — until his father rips the necessary crewman’s license right out of his hands.

While Gabriel Barre’s direction is sure-handedly superb almost every step of the way (as are Christopher Gattelli’s dance steps), he and the bookwriters should have made John lunge for the license or at least battle to get it back. Why is he so namby-pamby about his fate?

But he is and dutifully goes into the family business – which buys and sells African slaves.

That’s the first chilling moment of many. Just seeing a banner fly in with the information that there’ll be a sale today with “94 Negroes: 39 men, 15 boys, 24 women and 16 girls” is unnerving. Perhaps the sign isn’t historically authentic, but it appears to be.

The slaves look scared and scarred, but John scares us more because he is completely at home with selling these unfortunates. Not only is he utterly pragmatic but he also shows immense capability for rationalization when he insists that he’s giving slaves a better life here than they would have had if they’d stayed in Africa.

He tells this to his girlfriend Mary, which leads to a good confrontation, for she’s a member of The Freedom Society. But John could offer Mary’s Nanna as rebuttal, for she’s quite the Aunt Tom about slavery. Every now and then, however, she has some good common sense and wisdom shine through. Laiona Michelle plays Nanna with such dignity that we see she could have amounted to something extraordinary if she had only been given the chance.

Mary says John should be composing music, which make our eyes half-close as all-too-obvious foreshadowing on where the title of this show comes from. “All the talent in the world doesn’t mean anything if you don’t use it,” Mary cautions, in a line that’s a representative example of Giron and/or Smith’s banality. Exhibit B: After Father finds John incompetent at work, he rethinks his earlier decision and decides that “Perhaps the navy will knock some sense into you.”

Add to this “These eyes are not so old that they cannot tell when a man is in love,” said by John’s friend Thomas, who’ll later ask him “Do you think you are the first person to run away from a problem?”

Let’s put it this way: when I was transcribing my written notes onto my iPhone — which has a feature where it anticipates what word will follow the one just typed — it often offered me the precise word that Giron and/or Smith chose.

With John away, Major Gray makes his move with Mary. Unlike Lou Grant who didn’t care for Mary Richards’ spunk, Major says to this Mary, “You’re feisty! I like that!” The supposed joke (which Chris Hoch exacerbates) is that the Major thinks he’s as red hot as his uniform. “Call me Archibald,” he coos, embarrassing himself because he thinks he’s doing well with her while he should be able to see that she’s clearly not interested. The best musicals have self-aware characters.

They also have people for whom he can root and identify, which Amazing Grace suddenly doesn’t have when John does something unspeakable early in the second act. He makes such a horrible, unfeeling and cowardly decision that we come to hate him – just around the time Father turns out to be nobler than we would have assumed. Now that John appreciates him, the inevitable time comes for him to die. Giron and Smith offer the usual triptych of words said in increasing volume and urgency that’s used in stories where someone has just closed his eyes and died: “Father? (pause) … Father?! (pause) … FATHER?!?””

Only the hardest of hearts won’t respond when John literally comes face-to-face with the evil deed he did. It’s Amazing Grace’s most dramatic moment and Giron and Smith deliver on it.

There’s also an Act Two scene where the future King George III is seen at a play that is disrupted by dissidents. After the incident, he says of the playgoers, “They will leave the theater and they will forget.”

This line caused someone in my row to give a loud and knowing chuckle, one that said “Some critic is certainly going to mention that line.”

And now one has.

Whatever the case, Amazing Grace gives Josh Young the greatest audition piece he could ever choose, for it unquestionably shows that he can center and carry a musical. All night long, we wonder what wonders he could bring to a totally worthy show. We may very well see that happen, for we’re undoubtedly going to see a great deal of this young man in the future.

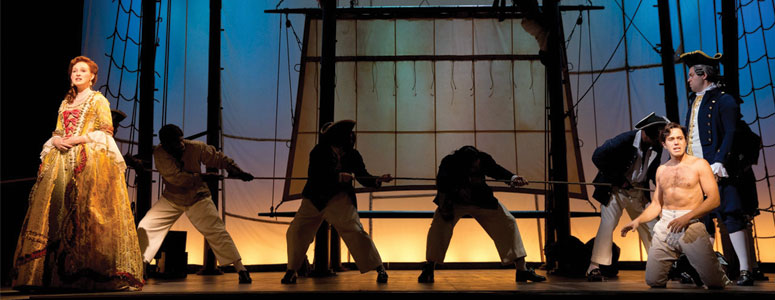

There’s one enormous problem with the set designed by Eugene Lee and Edward Pierce. The first scene takes place on a ship, so we see many masts sporting those little pegs on each side that allow sailors to climb to the top. But later at a fancy ball – and you know a show set in 18th century England will have a fancy ball to show off period costumes – each mast is still there with its pegs showing. Couldn’t these have been turned around in such a way to obscure the pegs and have them come across as columns? An elegant ballroom does not have a top mast, mainmast and mizzenmast.

And Christopher Smith’s score could be called Les Mizzenmast. Those who love the style of the Boublil-Schonberg classic will feel right at home. As Mary, Erin Mackey has a big second act number that’s admirable for the notes she hits rather than for the song itself.

Amazing Grace would have been better off if it had dropped Smith’s lackluster score, for the engaging subject matter would have made a stirring play, film or mini-series. On the other hand, if the likes of Peter Stone and Stephen Sondheim had attempted it in their prime, they would have been able to deliver an extraordinary musical.

Still, there is power at the end. Although we’ve all heard the show’s title song hundreds if not thousands of times, we never have and probably never will find it more powerful than it is here. The lyrics of “Amazing Grace” truly reflect the highs and lows of John Newton’s lifelong journey.

And yet … dozens of minutes before John writes and sings it, we and he hear the actual melody hummed by a group of Africans. One of them apparently wrote it and John Newton appropriated it for his lyrics. In other words, John has stopped stealing African bodies and has moved on to pilfering African music.