Those Judy Garland fans who hated END OF THE RAINBOW – and Lord knows there were thousands – are about to feel better.

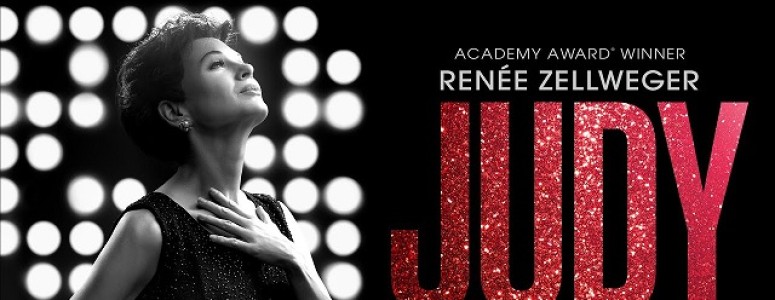

JUDY, the biopic starring Renee Zellweger — and based on Peter Quilter’s notorious play — is much more sympathetic to the controversial star.

At the Belasco, Garland was difficult from her first entrance. Do-this, Do-that, Get-me-this, Get-me-that, Do-what-I say, Don’t-question-me, How-dare-you, It’s-just-my-nerves – on and on and on.

Tracie Bennett gave a brilliant Can’t-look-at-her, Can’t-take-your-eyes-off-her performance. She supported Quilter’s thesis that Garland was an insatiable monster – albeit an inadvertent and unknowing one.

Garland acolytes loathed her and the play. Now they can go to their multiplexes with greater assurance that they’ll be given a more balanced look. Even when Garland erupts with volcanic force, she still isn’t as megalomaniacal as END OF THE RAINBOW painted her.

So little of Quilter’s play crops up in JUDY that one might suspect that Hollywood simply bought the property as a pre-emptive strike. Why risk having the playwright start a pesky lawsuit in claiming too many similarities with his script? Pay him off now and be done with it.

The biggest difference is that JUDY encompasses much more of Garland’s life. Quilter concentrated on those few days in December, 1968 when the star was in London preparing for yet another comeback concert. Instead, the film begins with a tight, tight shot of the middle of a female face.

It doesn’t look much like Garland’s. If this is the best Zellweger could do — and the closest lookalike that director Rupert Goold could find – everyone’s going to be disappointed.

Not to worry. The face belongs to Darci Shaw who plays Garland at sweet 16 on the set of THE WIZARD OF OZ. (Frankly, Shaw more resembles a Young Barbra or even Young Liza; only an occasional profile makes you see Dorothy Gale.)

A no-nonsense Louis B. Mayer matter-of-factly criticizes the teen in words that would devastate the thickest-skinned diva. Mayer flatly tells her that she isn’t as pretty or slim as other girls; he even mentions her competitors’ superior teeth. “But,” he does concede, “you have that voice.”

Mayer then points out how lucky she is to be a girl who could make her living as a Hollywood star instead of becoming “one of those cashiers, farmers’ wives, housewives.” Later he’ll even put down Garland’s father by using the F-word – the six-letter one.

The mogul’s threatening strategy frightens the lass. So when a publicist — cruel as a nun schoolteacher in the ‘50s — routinely offers Young Judy pills ‘round the clock, well, you know the rest.

END OF THE RAINBOW denied us the chance to feel for the woman who once was this girl. These achieve that.

Much later we’ll appreciate Edge’s showing that Garland wasn’t condescending to people and treated everyone the same, be the person mogul or maid. But first we cut to 1968 when Garland and children Lorna and Joey walk to their hotel’s front desk. All look as if they’re approaching the bench for sentencing.

They’re not surprised when Garland is denied the key for non-payment. As the kids, Bella Ramsey and Lewin Lloyd convey that they long ago stopped believing in their mother.

Here’s another chance to appreciate Garland when we see what a loving and doting mother she is. To save them, what’s left but to show up at the house of Sid Luft, ex-Husband #3 and the children’s father.

Rufus Sewell has little on-screen time, but enough to become as caustic as ex-spouses can be. Yet there’s no denying he’s got powerful ammunition when detailing how Garland’s professional failings had impacted both of them.

The only offer Garland is getting is from London – and the courts won’t let her take the kids out of the country. She has to accept the gig.

Garland isn’t there for more than two minutes when she’s giving an excuse not to rehearse. Then, in one of the film’s many imaginative touches, Garland picks up a sheaf of papers that cinematographer Ole Bratt Birkeland centers on. The top page details the many obligations Garland will have in the next few days. By then, we fear that she’ll do few or none of them.

“Fear” is the operative word. The difference between the play and this film is that the former made us sick of Garland while the latter has us rooting for her. More than an hour passes before Quilter’s irascible Garland emerges. By then, Edge’s screenplay has skillfully shown us what got her to this lamentable point. If we didn’t care about her when we walked in, we do now.

That happens again when assistant Rosalyn (an excellent Jessie Buckley), trying to be sympathetic after Garland hasn’t done well, gives her the rationalization that “You’ve been under a lot of pressure” – to which Garland somberly says “Since I was two.”

The camera is behind them in this scene where the two are walking. If you assume Goold is trying to keep close-ups of Zellweger to a minimum because she doesn’t resemble her, you’re wrong.

For all who have been saying “I can’t picture Renee Zellweger as Garland,” just one look, that’s all it’ll take, for you to say “Oh, now I can.”

Whether the result came by nature, make-up or plastic surgery, Zellweger’s face is Garland’s at least 85% of the time. Only occasionally does her actual trademark Look of Confusion break through.

True, a make-up artist’s getting the right hair, the correct lipstick application – and the many careworn vertical lines above the lip — certainly cement the illusion. That Zellweger is at Garland’s razor-thin weight (which had to be an accomplishment in itself) helps, too.

Yet more was required to replicate The Wonder That Was Garland and Zellweger captures all that in a performance that’s extraordinary beyond belief. The actress must have watched Garland’s appearances in all 32 feature films and assorted short subjects multiple times. She even takes pains to be left-handed, as Garland actually was.

Zellweger has the head that slightly shakes from side-to-side; the neck whose trajectory’s is much like a giraffe’s; the left arm that lifts seemingly involuntarily with a fist at the end. They’re all part of a body that’s now enduring a hint of osteoporosis.

The actress includes the smile that’s a mix of bravery and passion; the sudden and unexpected burst of laughter; the drag on the cigarette that reveals a chain-smoker.

When time comes to perform, Zellweger’s Garland looks completely out of gas so Rosalyn literally throws her in front of an audience. Zellweger goes into the right Garland walk, stalking across the stage with ownership and a triumphant I-can-still-do-it look.

Scriptwriter Edge provides Garland’s droll and intelligent humor; Zellweger adds the charm and charisma.

Fine, but what about her speaking and singing voice, which are the really most important parts of the impersonation? They’re both there, too. Note the correct tone when she says “mahvelous.”

No one was required to dub Zellweger’s singing, either. Standing ovations in the ‘60s were rare, and the idea of a crowd rising after an opening number – yes, after the FIRST song – was utterly unheard of. And yet, the way Zellweger does that song will make you believe that people did stand that night in London.

And yet, after that triumph, all she can think is “What if I can’t do it again?”

She can and does – and feels the lyrics of each word right down to her dynamic finale.

(And you know what that song is.)

So when her back is to us and she says “Since I was two,” we’ve seen Zellweger’s Judy-face enough to imagine what it looks likes when she’s saying it.

There’s another amazing moment that Zellweger accomplishes with her back. Soon after she reaches London, she’s on stage facing the theater’s auditorium while our point-of-view comes from Rosalyn behind her. When Garland fearfully notes that the sold-out theater has four balconies, Rosalyn asks how many Carnegie Hall holds, fully knowing that it has one more, but wanting Garland to say it.

Garland does: “Five,” she says. Note the way she breathes out the simple word which reminds everyone that that was almost eight long years earlier. She knows that she can no longer deliver what she’d achieved that night.

Not long afterward Garland meets Mickey Deans (admirably played by Finn Wittrock). Zellweger’s “Could I come home with you?” isn’t followed by “Please”; the expression on her face adds the word for her. So does the Take-me-to-your-bedroom look.

Deans is never portrayed as an opportunist or fortune hunter (what fortune?); this Mickey Deans actually loved her, although Wittrock’s face shows much wariness when SHE proposes.

Marrying helps her – for a time. She appreciates that Deans — destined to be her husband for all of 98 days – believes in her. Later, when he can’t swing a deal he assumed he could, she completely loses faith in him.

The screenwriter takes pity on Deans for we’ve seen Garland’s recent behavior that squelched the transaction. After Garland treats him unfairly, Deans holds his temper longer than many would.

There’s the Hollywood belief that if an actress can get a good telephone scene with the camera squarely centered on her face, she’ll get an Oscar. Zellweger might have wound up winning the prize even if this moment hadn’t been in the film. With it – and the way she maneuvers two heart-wrenching pauses that make Harold Pinter’s seem like split-second timing – the Academy must take her even more seriously.

The dozen or so songs are carefully chosen to make a comment on what we’ve just seen. (“I’ll go my way by myself.”) How we wish Garland would take her own advice and “Forget your troubles, c’mon, get happy.” And when she sings “Your gonna love me like nobody’s loved me” we nod in agreement, for that’s what we feel for both Judy Garland and Renee Zellweger.