As soon as the curtain rises on PASS OVER, we immediately have two questions.

What is there at the bottom of that center stage lamppost?

Is that a garbage bag or a human being?

Not until we see some movement can we be sure.

Playwright Antoinette Chinonye Nwandu and director Danya Taymor will pose many, many more questions in the ensuing 90 minutes. Here, though, they may be making a statement that the Black man who’ll slowly stand is one whom many would treat as garbage.

He’s Kitch, whose teenage years are already behind him. He and his twentysomething friend Moses (who’s standing upright) are killing time on a street and hoping not to be killed.

For in the midst of their chatting, bonding and laughing, they suddenly stop. They turn fourth-wall, raise their hands high in the air and show faces of sheer panic.

We don’t have a question on what’s happening. How sad that these young men feel that they’d better take no chances with the cops who are driving by. The lads know the now-famous names of victimized and murdered Black men as well as we.

“You scared?” one will eventually ask the other. The answer of course is “No,” for what young male ever wants to admit that he is? Yet this won’t be the only time when their faces youthen into those of very terrified little boys.

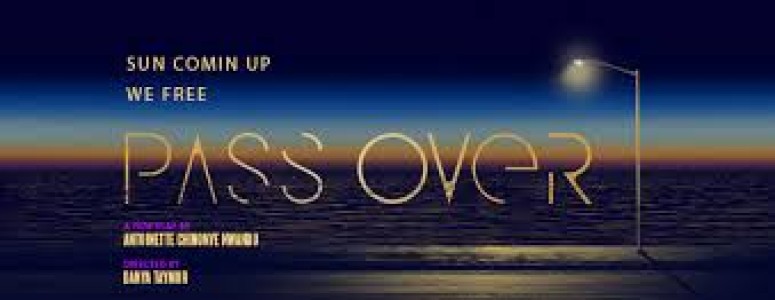

This is the world of Nwandu’s play that’s been graduated from the small Claire Tow Theatre in Lincoln Center to Broadway’s August Wilson Theatre on West 52nd Street. PASS OVER is a play you WANT to be dated.

Part of the tragedy is that both Kitch and Moses are naturally bright. They use air-quotation marks; they’ve also retained the quotations that they’d heard endlessly in school (“I can rise up to my full potential.”) Their parodies of Sunday school teachers are wickedly on the mark. By the time Kitch says “Bon appetit,” Nwandu has so established him as intelligent that we don’t doubt that this phrase would be part of his vocabulary.

If only they had food to follow the “Bon appetit” instead of appetites that need feeding. All they can do is fantasize about “lobster rolls, champagne and caviar” before admitting that even collard greens and pinto beans would be a treat. To say that their pockets are empty isn’t a metaphor; Kitch pulls out both of his inside-out and not even lint falls out.

Ah, but here comes a white passer-by who’s carrying an upscale picnic basket. Will he share the wealth?

“Mister” is unlike any Caucasian who’s ever wandered into a strange neighborhood and has encountered two young Black men. He’s never frightened for even an instant, which many whites would be when stumbling into unknown territory.

He’s borderline effeminate, too, jutting out his chin when making a point, punctuating a line with a quick bend of the knees and occasionally saying “Gosh!” and “Golly gee!” And what’s he doing when he suddenly plops himself stomach down onto the pavement and moves his calves back and forth, forth and back?

“I think you’re both delightful!” he tells the young men, who have actually said so little that this is a conclusion that he couldn’t possibly have reached. Anxiety isn’t what keeps Mister chattering; he believes that they want to know all about him. So he explains that he’s on his way to his mother’s house

Thus we can’t imagine that he got lost, as he claims.

Nwandu makes this white man as clichéd as Stepin Fetchit was as a black one. But is he Moses and Kitch’s imaginary conception of what they’d expect or believe a white man to be?

The Playbill provides an oblique cue: PASS OVER includes four different time settings dating back to “1440 BCE” and five different locales including “a desert city built by slaves.” So as for our playwright, where she stops, nobody knows for sure.

The first hint that we’re not dealing with reality occurs when Mister extricates the food from the basket. It’s beginning to look a lot like Christmas to the young men, as they see him take out one savory savory after another. Just as we start to suspect that the basket can’t possibly contain all that he’s removing from it, Nwandu gives us another surprise that’s purposely meant to be unbelievable.

The trick, not to be disclosed here, is more evidence that the young men are imagining this white man (while also commenting that there’s no end to the number of upscale treats available to him.) See, too, if Mister actually winds up giving them something.

So PASS OVER may offer more fantasies than those entering the mind of a married man who’s been faithful for 50 years. And yet, who’d bet that the scenes where the fourth-wall police drive by and the young men’s hands go up aren’t imaginary?

With a half-hour left in the piece, Kitch and Moses as well as theatergoers hope that the cop who enters is indeed one of their fantasies. Ossifer, he’s called, in the way that the overly intoxicated have been known to bumble the word “Officer.” He’s played by Gabriel Ebert, who also portrays the effete Mister. Now he gets the chance to show his range with his aggressive, you’re-guilty-till-proven-innocent smug attitude.

Namir Smallwood is Kitch, who doesn’t wear actual shoes, but still goes through the motions of shining his sneakers. So when he gets a look at Mister’s ultra-white, brand-new Nikes, he regards them as if they’re two bars of gold bullion.

So does the equally excellent Jon Michael Hill as Moses. The way he spits out the words “stupid, lazy, violet thug” reveals how many times he’s been accused of being that person. When he says “I’m going nowhere,” he means that he’s not leaving the premises, but the greater meaning doesn’t escape us. Yet Nwandu lets us decide if he is guilty as he’s charged himself or a terrible victim of circumstances.

Don’t miss the moment when Hill looks out at the audience and stares down those he can see from the stage. Here’s hoping you’ll be listening intently so you can fully glean what spurred it.

And yet, there is hope. PASS OVER reminds us once again that art has the power to bring people together. At one point, both black and white sing the same song – and (here’s a fine metaphor) even harmonize (at least until one lyric unnerves them.)

And speaking of unnerving, has there ever been a play (or even a street corner) that has employed the N-word as frequently as PASS OVER? It’s said more times than the Claire Tow has seats – meaning more than 200.

Many whites have been mystified why some Blacks routinely use this otherwise verboten word to describe themselves. Nwandu offers an explanation that will make sense to some but won’t convince others.

Onto a fascinating tidbit: Ebert’s understudy is Andrea Syglowski. Before you can say “Oh! Another man named Andrea, like Audrey Hepburn’s second husband!” no: Ms. Syglowski is a cisgender woman. If Ebert is ever out, many who have seen PASS OVER with him would probably want to see it again with her.

And many who hadn’t seen it would be more likely to think that her showing up as a white woman with a picnic basket would definitely peg her opening sequence as fantasy, for a real woman would not be blasé about where she’s landed and the two men she’s meeting. With the police force now boasting plenty of able-bodied women, however, Syglowski can’t even jokingly be described as “non-traditionally cast.”

Indeed, in the colorblind sense, this will be the Broadway season with the least amount of non-traditional casting. No, directors haven’t decided against the practice; the far better reason is that Broadway will be seeing so many plays with characters who are African-American. Although PASS OVER will close on Oct. , it will be remembered in that all-important month of April.