Have you ever heard the mere word “Advertising” get a big laugh from an audience?

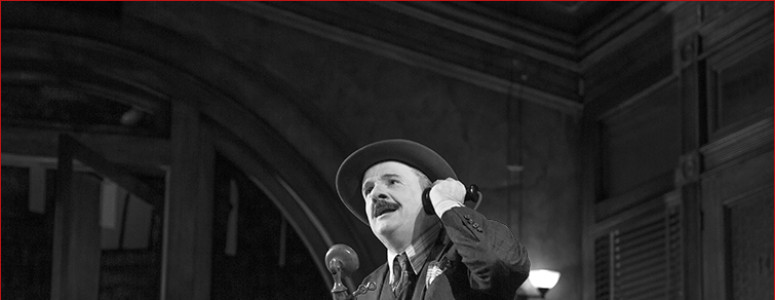

Here’s betting that it didn’t even get a titter when Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur’s THE FRONT PAGE debuted in 1928. But after John Slattery says it in the current revival at the Broadhurst, theatergoers guffaw. They gleefully want to acknowledge the star who made himself famous as one senior partner of Sterling Cooper on 89 episodes of MAD MEN.

Is this why Slattery was cast? The reason couldn’t have been that anyone would have thought he was right for the role.

Hildebrand Johnson is the MVP of Chicago reporters who’s assigned to cover the execution of cop-killer Earl Williams. But he’s recently fallen in love with Peggy Grant (Halley Feiffer) who’s convinced him to move to New York, marry her and take a “respectable” job in – yes – advertising.

Will Hildy really go once this big story gets bigger and then the biggest in Chicago’s recent history? “Love vs. Career” is one of the great themes in countless plays and musicals, but THE FRONT PAGE is the property that expresses it best.

Alas, we can’t say that of Slattery. His worst moment comes when he swallows the play’s best line. Just as Hildy is ready to leave for the Big Apple, both Earl Williams and all hell break loose. Hildy grabs the phone, calls his editor-in-chief Walter Burns, tells him what happened and says “Don’t worry! I’m on the job!” It’s usually a cry from the heart and soul that shows Hildy’s true colorful colors and how career can even trump love. Slattery makes it a mere toss-off with nothing behind it.

Pat O’Brien – presumably no relation this revival’s director Jack O’Brien — knew how to say that line in the excellent 1931 film version. He had the zestful energy befitting a 30-year-old man, which brings up the next problem with Slattery, who’s 54 and looks older because of his mostly gray hair. Indeed, Slattery seems perilously close to retirement age, which lessens his being so valuable to the newspaper. Even worse, the dialogue demands that Hildy make a smart-ass prediction about the other reporters’ futures — that they’ll be on the copy desk and “gray-haired.” Well, that’s the elephant calling the kangaroo gray.

Exacerbating this flaw is the Peggy Grant that O’Brien cast is Halley Feiffer, not yet 32 and looking younger. Thus the 22-year age difference seems even greater. A May-December romance was not what Hecht and MacArthur envisioned, so an April-January one is even worse.

O’Brien has also made Feiffer into such a shrew that we don’t want Hildy to leave the paper and get married. To be fair, the script has her at non-stop odds with her fiancé’s priorities. But a catch-more-flies-with-honey approach is sorely needed. In these scenes, Peggy must make soft-pedaled requests and not unfeeling ultimatums.

That’s especially true because Hildy later calls her “the most wonderful girl I’ve ever known,” augmenting that with “They come like that once in a man’s life” and adding “She never complained.” No, we can’t buy it when we see that she constantly complains. So when Hildy tells her “I don’t deserve you,” we agree, but for a reason that’s the opposite of what he means.

The character who needs to have a hardline approach is Mrs. Grant, Peggy’s mother who’s also traveling with them. O’Brien makes Holland Taylor play the mater in somewhat sympathetic fashion, having her emerge more befuddled than furious. That’s not a bad choice at all, yet a good-cop in Peggy and a bad-cop in Mrs. Grant would serve the play better. After all, Hildy won’t be living with Mrs. Grant (or will he …?)

Wait a minute, you’re saying – where’s top-billed Nathan Lane in all this? Alas, you’ll have to wait 105 minutes before he makes his entrance at the start of Act TWO. Some in the audience expected him much earlier, for when Jefferson Mays rushed in during the play’s opening moments, he got entrance applause. True, his Lane-like looks fooled the crowd, but only for a few seconds; the applause abruptly stopped when theatergoers realized that Mays wasn’t the man whom they really came to see.

Lane’s fine, although he could have added even more ferociousness than the ferocity he’s found. Ironically, his best move comes when he shows some sentimentality. After Hildy leaves, although Lane has his back to the audience, the way that he puts down his hat manages to convey exactly how much he’ll miss the man.

Broadway has missed Robert Morse for nearly 27 years, but the 85-year-old is far too advanced in years to be the father of high schoolers that the script says he is. In his final scene, the stage directions do state that he should enter “stewed,” but O’Brien might have gone more easily on this. Morse’s character has important information to impart, and Morse’s reeling around the stage would have him written off with a hasty “He’s drunk!”

Of the seven reporters for the other Chicago papers (yeah, those were the days!), three stand out: Lewis J. Stadlen, who’s always understood how to play vintage comedy; Dylan Baker, who’s almost unrecognizable (which is as great a compliment as any actor could get) and the aforementioned Mays as a full-fledged germophobe (and transvestite, if O’Brien’s wan sight gag is to be believed).

They’d be even better if O’Brien had properly directed them in another important moment: Sheriff Hartman (a wan John Goodman) states “Williams is as sane as I am” which spurs the reporters to quip “Saner.” Here it isn’t funny because the guys say it with self-congratulatory glee with a subtext of “Didn’t we just come up with a good one?!” Much more effective is the time-honored response of “Saner” said dully, drolly, matter-of-factly, as if to say “So what else is new?”

Well, this production of this great play is at least new, and we must be grateful that a 25-member cast can still be produced at the Broadhurst. Management knows the play’s worth, for the cover of the Playbill doesn’t merely give the title, but actually says “Hecht and MacArthur’s THE FRONT PAGE.” Even Shakespeare doesn’t get that kind of treatment from Broadway.