The words “Sean” and “O’Casey” often come to mind whenever two other words – “Irish theater” – are mentioned.

For the next few months, Irish Repertory Theatre on West 22nd Street will show it agrees. The august company, currently in its fourth decade, has already done three readings of O’Casey’s plays and will do nine more such events through the end of April.

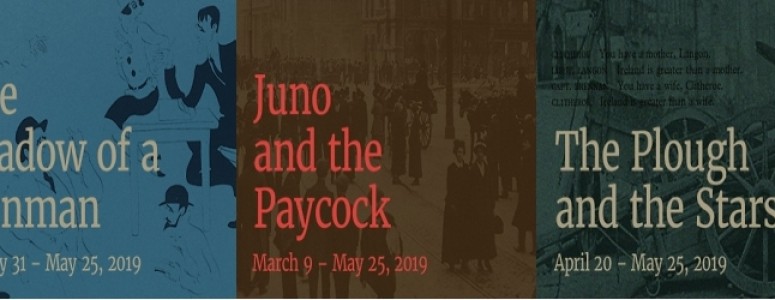

Better still, full productions of O’Casey’s three most famous masterpieces – THE SHADOW OF A GUNMAN (1923), JUNO AND THE PAYCOCK (1924) and THE PLOUGH AND THE STARS (1926) – will be presented between now and May.

At the moment, O’Casey is being very well-served by O’Reilly – Ciaran, that is, the theater’s producing director — who’s staged a potent production of GUNMAN. You’ll suspect you’re in good hands as soon as you see Charlie Corcoran’s evocative set.

This dark room in a down-and-out boarding house fits Irish Rep’s small stage with cramped coziness. The side of the mattress reveals stains — don’t ask – that complement the worn furniture.

What are bright and shiny, though, are two religious figurines that sit on the mantelpiece just below an equally sanctified portrait.

Yes, early in the century (at least) the Irish were particularly religious people. These Catholic characters believe misfortune happens because they’ve missed Mass or haven’t prayed enough to St. Anthony. Early on, Seumus Shields, a pedlar (sic; a Irish term for a salesman who sells shady items) awakes and asks roommate Donal, a poet, “What time is it?” only to hear “The Angelus went some time ago.”

The Angelus is a now-lapsed Catholic tradition. Bells would ring at noon as well as both six a.m. and p.m.; each time, fervent Catholics would stop what they were doing and pause in prayer. O’Casey suggests that this is one way that the Irish tell time – which tells us much about them.

However, these struggling Irish don’t simply blame God for their bad fortune, but take responsibility for it. O’Casey believed that the Irish have a hard time getting it together and shows that thorough many purposely passive characters. No wonder that the Irish Republican Army is having such difficulty in battling British troops.

So we understand why Seumus says “Did anyone ever see the like of the Irish people?” – especially after he and Donal aren’t savvy enough to distrust Adolphus Grigson, another tenant, when he comes in and asks if he can leave a handbag there. (Not a pocketbook, mind you, but a bag like the one in which Jack Worthing was found after he’d been left at Victoria Station — The Brighton Line.)

Donal and Seumus seem unduly naïve to us who live in the “If you see something, say something” era. Alfred Hitchcock prided himself on letting an audience in on dangerous items of which his characters weren’t aware; that isn’t quite the case here, for we don’t know what’s in the handbag. Chances are you’ll be more suspicious than those on stage, who’ve been assuming that the quiet-as-a-quiet-mouse Donal is an Irish Republican Army agent. O’Casey’s theme that paranoia can run rampant – but sometimes in the wrong direction – comes through boldly.

One who believes that Donal is “a gunman on the run” is boarder Minnie Powell. (Some women love bad boys, don’t they?) Actress Meg Hennessy does a fine job in how she shows how smitten she is with Donal. Baseball is often called “a game of inches,” but Hennessy makes her interest in Donal a game of quarter-inches as she ever so slowly and subtly moves closer to him hoping he’ll catch the hint. Meanwhile, James Russell does justice to the sensitive, forthright Donal who feels he’d best not get involved.

“Aren’t all the girls fond of poets?” an increasingly frustrated Minnie asks in justifying her forwardness. Donal’s retort must have scandalized 1923 Irish Catholic audiences: “All the poets aren’t fond of girls. “

At the risk of stereotyping, O’Casey gave another reason why the Irish are seemingly incapable of making profound changes and improvements. It’s a detail found near the end of many Irish plays of the ‘20s: someone staggers in roaring drunk.

Well, you might drink, too, if you worried that at any minute The British Army could burst into your home and make you guilty until you were most unlikely proved innocent. O’Reilly’s production keeps that suspense building with it-could-happen-at-any-second tension.

Ed Malone is Tommy Owens, a hothead who’s been deemed unfit for service; as a result, he can afford to talk big about how he’d kill this one and that one if he’d only have the chance. And then there’s Michael Mellamphy, doing quite well by the rough-and-tumble as Seumus who can’t stop talking and distracting Donal while he’s at his typewriter. (And you thought that when Sam Shepard wrote TRUE WEST that he was first to create this situation. No, O’Casey got there more than a half-century earlier.)

Seumus sleeps in his long-johns, gets up and puts his work clothes right over them. He doesn’t take a shower or bath, which may be understandable in those days when such an activity was relegated to Saturday night.

But after Seumus awakes, doesn’t he need to urinate like the rest of us? Guess O’Casey didn’t want to get that down ‘n’ dirty. He might have felt that after alluding to gay poets, he’d better quit while he was behind.