Oh, why not?!

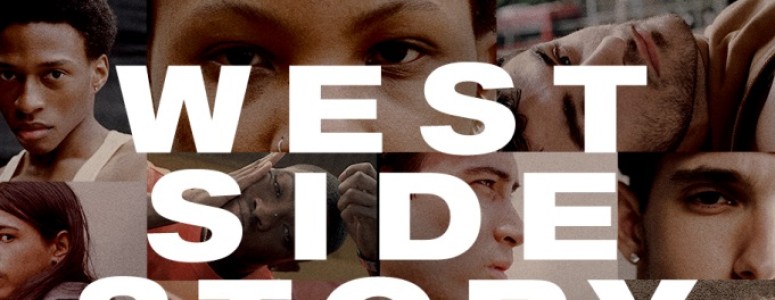

Let’s face it: WEST SIDE STORY, in their faithful 1980 and 2009 revivals, set few pulses racing with their business-as-usual approaches.

As a result, giving maverick director Ivo van Hove the chance to reimagine it was a good move. Those who know his work had reason to believe he could make the show as exciting as it must have been in 1957.

Consider that back then that the musical that opened just before WEST SIDE STORY was MASK AND GOWN, a harmless drag revue; the one that debuted after it was COPPER AND BRASS, an ostensibly fun-filled look at the New York police force.

WEST SIDE STORY offered a very different take at those who have been called “New York’s Finest.” Here, in this radically new production, Lieutenant Shrank certainly doesn’t believe that Puerto Rican lives matter. In a time when many of us have become more sensitive to minorities, his all-too-frank words scald more now.

So does van Hove’s interpretation. He begins with a bare stage and keeps to it. There will be so little scenery that all of it could fit in a mid-sized U-Haul.

Smoke creeps in, and where there’s smoke, there will be plenty of fire. And where there’s van Hove, there’s video. So much is shown on screen that if it weren’t for the prices, you might think that you’ve walked into Steven Spielberg’s upcoming remake.

Some have carped that the videos distract and minimize the people on stage. Let’s say you’ll be sidetracked if you care to be. You’re in control of when you choose to watch the video and when you’ll concentrate on the on-stage action.

Granted, many of the scenes are set so far upstage that they seem Lilliputian in contrast to the stage-filling videos. Much of the time, however, van Hove places his performers at the lip of the stage where they dominate.

The video approach is another step in the rock-concertization of Broadway musicals. Those who have gone to Madison Square Garden to see Springsteen know that big video screens will be peppered around the arena so those in the upper reaches of the building will be able to see what’s happening on the faraway stage. The Broadway Theatre is one of our biggest houses, so those in Row R of the rear mezzanine will be able to experience the show better than they might have assumed when they bought their tickets.

Better still, the video shots aren’t just head-on as if taken from the audience; often they’re from a different angle as a result of von Hove’s placing the videographers in the wings. This mix-and-match approach is often rewarding and exciting.

If there were a Tony for Best Set Decoration of a Video (and don’t bet against it happening someday), this production would get it. Doc’s store is an unruly riot of crammed-together items. The dress shop shows a number of women at sewing machines virtually on top of each other, reiterating that it’s a sweatshop. Maria’s bedroom has peeling paint and a low-rent tenement feel.

One downside of the videos, though, occurs when the gangs are shown in close-ups, for we see the pearl-shaped head microphones in the middle of their foreheads. Ironically enough, I attended on Ash Wednesday, and these black marks near the toughs’ hairlines looked as if the gangs had been to church and had gotten dusted.

Later a close-up video of Maria’s trying on her new dress reveals a microphone pack resting in the middle of her gluteus maximus. You might not notice it, though, for you may be instead questioning the dress that costume designer An D’Huys has given her. It isn’t nearly as lovely as the one Natalie Wood sports in the Oscar-winning film.

Is Maria’s enthusiasm over this only-off-the-rack-worthy garment meant to suggest that she doesn’t have much taste in clothes? Should we infer that Anita doesn’t have the ability to design anything impressive?

Even those all in favor of van Hove’s high-tech approach might balk at his having a camera-on-shoulder videographer actually come right on stage during the rumble. As off-putting as it is, you might not even notice him because of the far more graphic representations of violence.

Some fights are said to be gloves off; during this rumble, it’s microphones off; the grunts and pain coming from the stage are unamplified and yet speak for themselves. You’ll still hear the men suffer and will certainly see them in vivid close-ups.

The videos also reveal that the gangs’ bodies have more tattoos than there are seats in the biggest Theatre Row Theatre. (Wonder if those auditioners who’d already had tattoos had an edge in getting cast?) Tony’s had a vivid one imprinted on his neck, and must now have regrets, for it represents his past and not his future.

And he is forward-looking. Bookwriter Arthur Laurents knew that a good way of showing how determined he is to advance and leave his gang days behind him is to make a new sign for Doc’s convenience store. Here it’s a classier one than we’ve seen in other productions. But considering how messy the store is, Tony would be better advised to reorganize its wares.

And yet, despite his newfound ambition, Tony is still drawn to Riff, his Jets co-founder. The theories that the two have had homosexual relations is one that van Hove seems willing to entertain. More than once the video shows the two men nose-to-nose with less than a quarter-inch space between them. Each seems to be making a great effort not to plunge forward and kiss.

Ever wonder why the milquetoast known as Baby John has been accepted by the Jets? Matthew Johnson is directed to be even weaker here, yet he’s not the least butch person on stage. In the first dress shop scene we spy in the background a Puerto Rican who appears to be an employee dressed in androgynous clothes. During “The Dance at the Gym,” he’s seen dancing with another man which seems to bother no one.

Yes, this WEST SIDE STORY is set in the more liberal here-and-now (Doc’s store sells lottery tickets), but wouldn’t at least one gang member feel compelled to express his homophobia? At the very least, the Sharks would want to distance themselves for this young man; at the very most, they’d give him a pummeling every chance they got. Even Jacob Guzman’s Chino is rougher than Jose De Vega’s shy guy in the film; he seems capable of, you should pardon the expression, straightening out the guy.

During that “Dance the Gym” green lights illuminate one gang and purple ones shine on the other – but that still doesn’t mean that you’ll be able to differentiate the two teams. Previous iterations of WEST SIDE STORY made clear who were Jets and who were Sharks. That’s harder here, for those of various nationalities populate each gang.

If the Jets are so natively prejudiced, would they choose a black man as their leader? Chalk up the casting of African-American Dharon E. Jones as non-traditional casting and leave it at that. He probably got the job for the best possible reason: Jones is terrific (especially considering that he was a last-month replacement when the first choice for the role became injured).

Choreographer Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker doesn’t have Tony and Maria immediately see each other at the gym and experience Love at First Sight. She takes her time and lets them dance. What’s amusing (and believable) is how awkward Maria’s attempts are. Well, didn’t she tell us that this is her first dance?

What isn’t typical of WEST SIDE STORY is that this Maria is hot to trot. Shereen Pimentel is even more hands-on carnal than Isaac Powell. By the time they meet, though, this won’t surprise you as much, for you’ll have noted that Tony is awfully namby-pamby. Many have complained that the film’s Richard Beymer didn’t seem to be capable of leading a street gang; Beymer’s a serial killer compared to Powell, who’d be an ideal Doody in GREASE.

Perhaps Powell was cast because of his terrific voice. (Pimentel has one, too.) When he sings “Maria,” he tries out many inflections in the dozen or so times before he finds one he likes; that’s the lengthy one he sings over and over again. It’s a detailed performance.

Another perceptive van Hove touch is his showing us Riff ruefully observing the couple. He knows that if there ever had been a chance that Tony would rejoin the gang, it’s now evaporated.

After Tony and Maria meet, De Keersmaeker has the gangs stand still behind them and stare at them. That may be some sort of symbolism on the choreographer’s part, but in a production that’s been intent on establishing gritty reality, we can’t accept that this silent staring would happen.

And yet, a similar move from De Keersmaeker and van Hove gets better results. As the lovers sing “Tonight,” the Jets and Sharks slither on stage and surround them. But they’re not really there; the point is that Tony and Maria have these people in the backs of their minds; forgetting about them won’t be easy.

Much has been made of what van Hove has taken and discarded from the film version. He was wise to keep “America” as it was the in the film – Shark Men arguing with Shark Women – as opposed to the stage play’s only having the women bicker among themselves.

Here the choice of video is wrong, for shots of Puerto Rico’s beaches and palm trees makes the place look like paradise. Better to have shown the island’s tenements inside and out and have them resemble the ones in New York; that would underline that there isn’t much difference in poverty no matter where you live.

While van Hove was making changes, though, he should have adhered to the movie’s swapping “Cool” with “Gee, Officer Krupke.” For one thing, “America” is such a dynamic production number that “Cool,” which immediately follows it, can’t top it, no matter how frenetic De Keersmaeker makes it.

(Besides, “Cool” shouldn’t be frenetic, for Riff’s point is that the Jets shouldn’t get too worked up. It’s the same discrepancy seen in KISS ME, KATE’S “Too Darn Hot,” which should be cool, too. Who dances his feet off in oppressive summer weather?)

“Gee, Officer Krupke,” which offers musical staging rather than genuine choreography, is better in the early spot, for the Jets still believe themselves to be on the top of the world and have time and opportunity for levity. In this heavier and more realistic production, it more than ever doesn’t seem to be what would be on the survivors’ minds. The use of such expressions as “Golly Moses” and “Gloriosky” are too tame for these men at this point; “Leaping Lizards” is a line best relegated to Annie Warbucks. But if the number occurs before the “War Council,” we can accept it as a divertissement.

As for “I Feel Pretty,” van Hove did better by eliminating it than squandering it as the film did where it’s just a numba for Maria. It had so much power in stage play when it opened the second act with Maria’s joy at being in love, unaware that her brother has been killed and that life will now offer heartache for some time. Whatever the case, here’s betting that in a driving and speedy 95-minute intermissionless production, you won’t miss it.

Equally reported and discussed was van Hove’s decision to drop the “Somewhere Ballet” (which has essentially been replaced by the cast walking from stage left to stage right). As the action pulses on, here’s another wager that you won’t yearn for that, either.

No, elegant choreography isn’t here. The attempted rape of Anita is no longer a dance but a realistic melee. You’ll even see a sliver of dorsal nudity that leaves no doubt what a certain Jet intended.

Amar Ramasar scores mightily as Bernardo, the only Shark whom Laurents gave any Shark to shine. Yet Yesenia Ayala makes little impression as Anita, a role that usually gets the performer who plays it a Tony nomination (and even once got a win).

And then there’s Anybodys, the outsider who’s desperate to be accepted by the Jets but only gets their contempt. So when one of the gang finally gives her a compliment for genuinely helping, she should act (as Susan Oakes does in the film) as if it’s the highlight of her life. In this production, Zuri Noelle Ford is utterly matter-of-fact.

Here’s another misstep from costume designer D’Huys. Anybodys shouldn’t be in a bare-midriff outfit that has the same bra-like top that the other girls routinely wear. This would-be Jet would eschew anything that vaguely resembles women’s clothes.

Considering how searingly raw the production is, one wonders if Stephen Sondheim was approached to coarsen his lyrics. If so, did he refuse? Frankly, Sondheim should have changed them for the 2009 revival or even the 1980 one. It’s a surprise that he never has, for even in the relatively innocent Eisenhower-era, he envisioned “Gee, Officer Krupke” ending with “Fuck you!” (Bernstein suggested the epithet that wound up on stage.) So those “buggings” that we still hear in “Jet Song” should now reflect the language that we routinely hear from kids walking home from middle school.

In the end, it’s still WEST SIDE STORY with Leonard Bernstein’s dazzling music that has somehow always managed through the decades to never seem dated. Those who saw the two previous major revivals probably stopped thinking about what they’d seen soon after they arrived home. That won’t be the case after they see what Ivo van Hove has rendered.