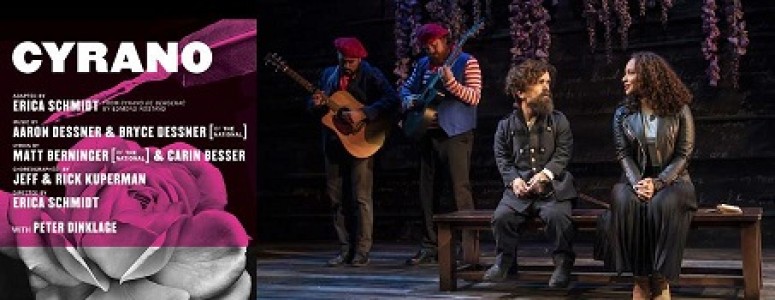

With Peter Dinklage as the title character in this new musical simply called CYRANO, you might assume you’ll see a fascinating new twist on Edmond Rostand’s classic.

Won’t his four-feet-five frame and not his nose be what makes him feel he couldn’t win Roxane?

Granted, with this approach two magnificent speeches would be lost. The first happens after Cyrano encounters a character known as “The Bore” who notes that Our Hero’s nose is “big.” Cyrano trumps his deuce by then acknowledging 18 different and dynamic ways that The Bore could have more effectively and colorfully mocked his proboscis.

What would also go if height were the problem is the sequence where Cyrano is telling of his recent exploits. Here Christian, one of his new recruits, interrupts and mocks that nose after virtually every sentence. All those who are listening assume that Cyrano will soon pull out his sword to silence both the insolence and the man’s life.

No – once Cyrano learns that Christian is the handsome solider whom Roxane loves, he won’t harm him. That’s how much he loves the lady; he’ll endure the slings and arrows of outrageous remarks rather than kill the man she wants.

Perhaps adaptor Erica Schmidt also felt that last sequence was a problem. After all, would a new recruit be so brash that he’d dare criticize someone whose military rank is above his? So in addition to dropping the sequence with The Bore, she also eliminates the one with The Boor.

Don’t assume, though, that decision was made because Schmidt was swapping the nose issue for the height one. Although there are only two references to a lengthy nose in the entire 130-minute musical, this remains the reason that Cyrano believes that Roxane could never love him.

Dinklage wears no appendage of any kind; his actual unadorned nose is on view. Nor does the height issue ever come up in any way; we are supposed to see Cyrano as a man of normal height with an atypically long nose.

Perhaps Dinklage and Schmidt wanted to make a statement that height is no barrier for two people to fall in love. They’ve certainly proved it by their own 14-years-and-counting marriage. Whatever the case, we have another example of non-traditional casting.

It’s a non-traditional musical, too. Although the pleasant music from Aaron and Bryce Dessner and the awkward lyrics by Matt Berninger and Carin Besser are plentiful, few actually come across as songs. They’re mostly snippets; dialogue weaves in, out and around them. Never once during last Saturday evening’s performance did the attendees applaud after a single one of them had concluded.

That’s what Schmidt, who staged the show as well, wanted. She’s directed the cast to immediately start speaking at the end of every song (again, if you can call any of these pieces “songs”).

The musical theater has seen many, many attempts to musicalize CYRANO DE BERGERAC. Broadway has played host to three and would have employed four others (at least) if their producers hadn’t closed them on the road. Talents as disparate as Victor Herbert and Frank Wildhorn have tried it. None has yet to do it justice.

The reason often given is that the play itself, which Rostand wrote in rhyming couplets, is already a musical. Sondheim in his prime could have possibly taken that speech in which Cyrano cuts down The Bore and made it into an astonishing one-person musical scene. It might have rivaled “Rose’s Turn” as one of the all-time great musical moments.

What Schmidt has retained is Rostand’s second-most unbelievable plot point. We’ll later examine at the one that’s the most hard to swallow, but for now, let’s look at what might be the most over-the-top assertion in all dramatic history: Cyrano faces a hundred sword-fighting adversaries and all by himself (yes: all by himself) kills them all.

However, Schmidt has shown imagination in other instances. De Guiche is not the matchmaker intent on getting his choice of husband for Roxane. Schmidt has eliminated him as the middle man and has made him the one who expects to take Roxane to the altar.

She’s not at all interested. When we first meet her, she sings that she’s actually looking for “love at first sight.” We may question her values, but at least she knows (or THINKS she knows) what she wants. And she’ll get it through Christian.

Here it’s pronounced in the way people refer to a member of certain religions: Christian, not “Chris-tee-ahn,” the way the French say it — and the pronunciation that’s been used for the last 122 years.

Indeed, where and when is this CYRANO set? The program denies us both time and place although a song mentions the word “Southern” a few times. But is that Southern France, Southern Florida, Southern Finland?

Costume designer Tom Broecker has De Guiche in a suit that’s decidedly contemporary American. The actor whom Cyrano torments in no longer Montfleury but Montgomery. The expression “O.K” – which didn’t enter the lexicon until 1839 – is sung twice here.

Women are seen in the military, too. This may just be a case of needing more bodies to fill the stage of the ample Daryl Roth Theatre. Yet the way Schmidt handles the actresses, they seem to be genuine soldiers and not stand-ins.

So we’re in the 21st century? Don’t be so sure. The men are still carrying swords. Roxane has a chaperone, as she does in the original. What young woman has one today?

And when Roxane decides to live out her life in a convent, the nuns are dressed much in the way they’re clad in THE SOUND OF MUSIC. The few nuns that are left today instead wear modest street clothes with nary a habit nor wimple.

Dinklage has always been an excellent actor, as he proves again while striding the stage with authority. He doesn’t offer much panache, which may disappoint some, but that quality has caused too many actors to play the role hammily. One needn’t worry about that here. As for his singing voice, it’s an amiable baritone that’s somewhere between Leonard Cohen and Barry White.

Jasmine Cephas Jones is a wonderfully restrained Roxane. Schmidt gave her something exceedingly dramatic to do before the final curtain, which she handles splendidly.

Blake Jenner is facially able to convey the two qualities that define Christian. He’s handsome but can contort that face to show genuine stupidity.

Richie Coster is De Guiche, made to look dull so that Roxane couldn’t consider him a romantic candidate. Coster excels as an unappealing man who, like many of his ilk, doesn’t realize how unappealing he is. Schmidt and the collaborators smartly have him eventually face reality in both dialogue and song, which Coster handles well.

And that earlier reference to Rostand’s most unbelievable plot point? It takes place when Roxane is on her balcony and Christian is below, trying to say romantic sentiments to her. He can’t, so Cyrano hastily takes over and does the talking for him.

Now it’s been established that these two have known each other since they were children, so why wouldn’t Roxane recognize Cyrano’s voice? After the play had premiered in Paris on Dec. 28, 1897, Rostand must have spent much of 1898 using the expression “suspension de l’incredulite” – “suspension of disbelief.” Schmidt and her collaborators have either seen no problem with the scene or couldn’t find a way to fix it.

Know who did? Deaf West Theatre of Los Angeles.

Stephen Sachs, in a version set in the here-and-now, made his Cyrano deaf and Christian his hearing brother. Because they were siblings, Christian had learned American Sign language so that he could communicate with Cyrano.

As a result, this balcony scene had Cyrano out of Roxane’s sight but close enough to Christian so that he could silently sign the romantic words. Christian “read” them and conveyed them in his own voice.

By the way, Deaf West had originally planned to do a CYRANO musical but settled on a straight play. Given the imagination in Sachs’ adaptation, if the company has pursued its original plan, it might well have been the first to make a hit musical of CYRANO DE BERGERAC.