Theatergoers aren’t the only ones who should see George C. Wolfe’s current production of THE ICEMAN COMETH.

Every director as well should take in his shrewd mounting of Eugene O’Neill’s epic.

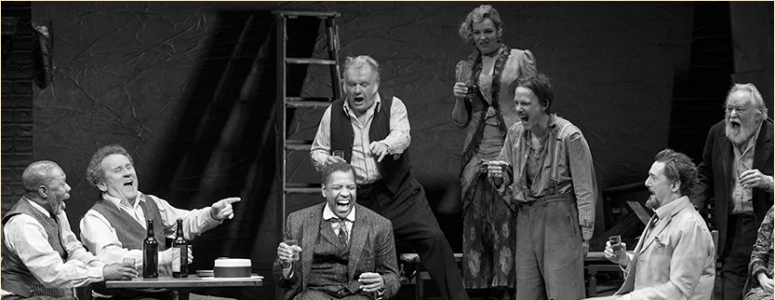

Wolfe displays his show-biz smarts in the way that he blocks the many actors in the drama – by placing the actors and the action close to the lip of the stage, virtually on top of the first row.

This allows theatergoers to more easily see the actors and, just as importantly, to hear them and not miss a word – each of which is extraordinarily good.

Trouble is, even the most experienced and attentive theatergoer could find his mind wandering if Wolfe had placed them near the theater’s back wall (as director John Tiffany all too often does in the HARRY POTTER plays).

Because we’re dealing with a drama that comes close to clocking in at four hours, we need every bit of help to stay with it. Wolfe’s staging technique ensures that we do.

O’Neill set his mammoth work in the type of place he knew well. Harry Hope’s seedy bar is in downtown New York circa 1912. “You couldn’t find a better place for lying low,” says Larry Slade. David Morse says it with a mix of resignation and shame. Most of the time, though, he’s able to convey his feeling of “Where did my life go?” and “How did it happen?” without saying a word.

Harry’s Bar could also include the words “and Hotel” on its shingle, for many a customer has a room there. That isn’t the only place each sleeps, for many feel free to nap at tables. Harry can’t complain, for he’s in the forefront of the snoozers.

Those still awake are seen unsteadily shaking although the shakes that twentysomething Don Parritt (the fine Austin Butler) experience aren’t the result of too many down-the-hatches of demon rum. They come from the anxiety he feels when approaching Larry Slade, who once had an affair with his mother. Although Don looks young, he’s been old inside for many years. Now he hopes that this confrontation will confirm what he’s often suspected: Larry is his father.

Morse, who’s superb as Larry, often has his hands in his pocket, which may merely be his way of getting comfortable or a metaphor of his hiding something. All night long, using a voice that sounds prematurely gray, he keeps us guessing whether or not he’ll ‘fess up to Don, stay mum or turn out not to be the lad’s father after all.

O’Neill tells us a great deal about Larry by having him come out with an observation about carbolic acid. Yes, Larry once was something more than he is now.

The key words in that last sentence, though, are “once was.” Indeed, if you try counting how many characters in THE ICEMAN COMETH say “I was,” you’ll have quite a job ahead of you.

O’Neill even establishes that the bar itself was once a nice place. Set designer Santo Loquasto shows us how long ago that was by the shriveled wallpaper that mirrors the drunks’ shriveled lives.

Some brought their troubles on themselves. Pat McGloin (a pensive Jack McGee) was taken off the police force because he was on the take. Bad fate sunk others. If frequent theatergoer Hillary Clinton attends, she’ll find herself nodding in sympathy with Harry (the poignant Colm Meaney), who’s still mourning “I would have won the election” – and whose losing took him out of every race life has to offer.

If you have doubts that Willie Oban (an effective Neal Huff) wasn’t graduated from Harvard as he claims, O’Neill believes he was by stating this in his list of characters. Having Willie lie would be an obvious choice, but O’Neill wanted to stress that even acquiring a sterling education isn’t a guarantee of success.

To paraphrase Sally Bowles, “Well, that’s what comes from all that liquor and liquor.” It once again lives up to its reputation as “the great equalizer” that can decimate the educated and wealthy as well as the ignorant and poor. Parents, if your teens are already drinking too much in clubs or cars every weekend, take them to this cautionary tale.

Prepare them for the ethnic slurs, however, that abounded in the early 20th century. Back then, those branded by the remarks didn’t simply tolerate them; they fully expected to hear them and accepted them as doleful truths.

The play is a bonanza for character actors whose looks and bodies would never launch a thousand ships. Frank Wood as Captain Lewis proudly shows his battle scar, for it’s the only tangible proof that he ever achieved anything. Wood’s heavy, one-step-at-a-time shows he isn’t the man he was.

The excellent Reg Rogers is Jimmy Tomorrow, so nicknamed for he plans to ask for his old job back “tomorrow.” We know the sun will not come out for him in the next 24 hours or ever.

Ed Mosher is twice the procrastinator that Jimmy is, for he says that he’ll hit up his old boss for his past position “in a couple of days.” Because Ed’s previous occupation was a circus performer, Wolfe (or one of the show’s casting agents) made an inspired choice: Bill Irwin.

How much money did Bill Irwin once spend to have each of his 206 bones removed? Although Ed’s currently a has-been, Irwin startles when he gets a suitcase out of his way by merely maneuvering a deft leg and shows that he still has his eloquent Body English.

Costume designer Ann Roth has him dress nattily down to his bow tie. Thus Ed demonstrates his need to at least look respectable.

But clothes don’t in fact make the man, so his sharp looks make us feel Ed’s tragedy even more. Of all the losers in the place, he has the best chance of making a comeback. Although he keeps assuring everyone that he will, we can’t bring ourselves to believe him, not with always carrying a glass in his pocket. He may not be ready for real life, but he’ll be ready in case he happens to stroll by a table where a bottle is being opened.

(And one often is. Birthdays are cherished here, for they give everyone another opportunity to raise a glass.)

Don’t bet or any of the others to come out of their hole-in-the-wall. They very well know that if they show up at some establishment for an interview, they’ll be lucky if they’re asked a couple of perfunctory questions before they’re shown the door. Better to keep the fantasy alive that if they DO re-apply, they’ll be greeted with both open arms and the benefit of the doubt.

Danny McCarthy’s Rocky shows the frustration of every bartender who’s ever had to break up a fight, cut someone off or endure streetwalkers Pearl and Margie, the self-proclaimed “tarts” who won’t accept the term “whores.” The dictionary gives us only one definition for the latter word but two for the former – so they prefer to relate to the delicious pastry.

One other woman invades the premises: Cora (the ever-nifty Tammy Blanchard), who unabashedly brags about stealing with the pride of pulling off the crime so easily.

By now you must be saying, “Hmmmm, I thought this was the play in which Denzel Washington is starring, but I must be wrong because he would have been mentioned by now.” All in good time, my dears – and Washington, in accordance with O’Neill’s script, takes his own good time in entering as traveling salesman Theodore “Hickey” Hickman and not until a full hour has passed.

The drunks are ready to sing “Hello, Hickey!” with the enthusiasm of Harmonia Garden waiters. He’s always been known to crack jokes about the iceman fooling around with his wife while he’s on the road. This time in town, however, he’ll be the iceman who’ll chill the slackers to the bone.

First he shocks them by refusing a drink which he pooh-poohs with a dismissive hand and a matter-of-fact “I don’t need it anymore.” He later adds “Don’t let me be a wet blanket” which isn’t enough in this wet bar. There’s the increasing uneasiness we’ve all felt when we see that an old friend has changed and now is not remotely the person we knew and liked. Worse, Hickey demands that all of them rid themselves of their “pipe dreams” and face who they really are.

Some of the time, Washington gives magnetic smiles that lead to hearty laughter.

Never mind all that of tongue-waggin’ about going “on the wagon” and insisting that “I can stop any time I want.”

That you can’t go home again is depressing enough; to learn that you can’t go back to work again is another knockout punch. Even a walk around the block is too much for one man.

“There isn’t enough liquor in the world to keep that nagging truth from not occurring to you,” says Hickey with a Bible Belter’s evangelical fervor, which is just what the part requires – nay, demands. When he tells what happened between him and his wife, he lifts up his head and faces the barflies to show he’s going to find the courage to go on.

Wolfe’s edge-of-the-stage blocking does fail in one respect. Hickey pulls up a chair, places it center stage and sits facing us as he delivers his final soliloquy (wonderfully, in fact). And yet, this staging has the men facing his back for many long minutes.

One could argue that Hickey is too afraid to confront them; still, at least one of the men wouldn’t sit still and would walk forward to see his face as well as hear what he’s saying. And wouldn’t another demand that he turn around when speaking to them?

Still, star-gazers won’t mind having Denzel Washington right in front of them, will they?

What a shame that THE ICEMAN will goeth when it completes its limited engagement on July 1. Well, movie stars are busy, aren’t they? Considering the worth of both play and production — and the challenge met in doing it well — let’s count our blessings that it’s here at all. A play about wasting time is a valuable way to spend your time.